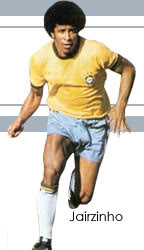

Name: Jair Venture Filha

Born: December 25, 1944, Duque de Caxias, Rio de Janeiro

First Professional Club: Botafogo

Jairzinho – The Hurricane

Compilation: The Best of Jairzinho

Jair Ventura Filha was born in the northern Rio suburb of Duque de Caxias on Christmas Day in 1944. His prodigious speed and strength on the ball was quickly spotted by the coaches at Botafogo where he signed as an amateur in 1961 at the age of sixteen. He turned professional shortly after winning a gold medal for Brazil in the 1963 Pan-American Games. It was at Botafogo that he had been first called Jairzinho, ‘little Jair’. The name distinguished him from the then more famous international Jair da Rosa Pinto of Portuguesa. It was on the terraces of the Maracana· that he won his distinctive nickname furacao, the hurricane.

With Gerson, Tostao,and Brito, Jairzinho had been one of the new generation to witness the humiliation of Goodison Park at first hand. He played in all three matches in England in 1966 but offered little or no evidence of the greatness that was to come.

By 1970, however, his star was in the ascendant. He had scored freely in the eliminators and had developed a good understanding with Gérson and Pelé in particular. Only Rogério offered a serious threat to his position on the right wing. By the final warm-up in Rio against Austria, his rival’s indifferent form and injury problems had effectively ended his challenge.

By 1970, however, his star was in the ascendant. He had scored freely in the eliminators and had developed a good understanding with Gérson and Pelé in particular. Only Rogério offered a serious threat to his position on the right wing. By the final warm-up in Rio against Austria, his rival’s indifferent form and injury problems had effectively ended his challenge.

Jairzinho arrived in Mexico determined to make amends for 1966. He was one of the players to benefit most from the Cooper Tests and Captain Coutinho’s disciplinarian training regime. Photographs of a shirtless Jairzinho at the training camps reveal a heavily muscled upper body and a powerfully built all-round athlete. In the sprinting tests he was comfortably the quickest of the 22-man squad over 50 metres.

From the opening match against the Czechs, the quiet man of the squad did his talking on the pitch. Jairzinho scored twice, first collecting a Gérson probe, flicking the ball over Viktor’s head before volleying extravagantly home, then crowning an irresistible, barnstorming run down the right with a perfectly placed shot inside the right-hand post. From then on he could not lose the goalscoring habit.

He scored again against England and Rumania in the group matches and Peru in the quarter-final. In Gérson’s absence, Rivellino and Paulo Cézar had taken over the role of provider. Both provided passes that gave him the half-a-yard headstart he required to skin defences alive. Only Bobby Moore, with the most perfectly timed tackle of the tournament, worked out a way of curbing him.

Yet there was much more to Jairzinho’s game than mere bullish power and pace. No one suffered more from the Uruguayan tackling in the semi-final. It was a measure of the restraint Zagalo had instilled in him that he failed to react once. Instead he replied in the best manner possible, latching on to an impeccable through ball from Tostao to outrun Mujica and score what would prove the decisive goal in the match.

His contribution to the Final illustrated his abilities without the ball too. Against Italy Jairzinho’s most effective work was done in drawing his man-marker Facchetti out of position in the middle of the pitch. Carlos Alberto wreaked carnage in his wake.

The reward for his selflessness came in the seventieth minute. As he forced Pelé’s knock-down over the line, Jairzinho’s place in history was assured. No player before or since has matched the flying furacao’s record of scoring in every match of a World Cup finals stage. In the cat-and-mouse climate of modern World Cups, it is hard to see how anyone ever will.