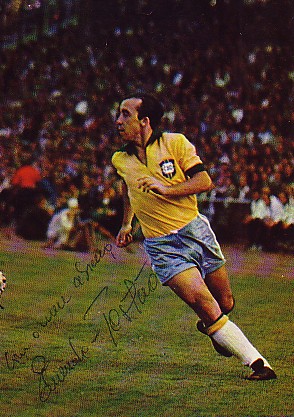

Name: Eduardo Goncalvez de Andrade

Born: January 25, 1947, Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais

First Professional Club: America (Belo Horizonte)

Tostao: The Little Coin

Eduardo Goncalvez de Andrade was born in Belo Horizonte on 25 January 1947.

Eduardo Goncalvez de Andrade was born in Belo Horizonte on 25 January 1947.

‘Aquarius,’ he smiles as he pours coffee from the silver pot his empregada, or housemaid, has placed on the table for him. ‘I am a very rational person, I analyse things and come to rational conclusions. At the same time I am a critical person, ironic, very quiet, introverted. I speak a little but I don’t keep quiet,’ he sums up with a sagacious nod.

Eduardo’s family was middle class, his father worked in a bank in Belo Horizonte and played amateur football for one of the city’s clubs, América. He passed on his love to all four Gonçalvez brothers. ‘I grew up in a passionate football atmosphere,’ recalls Eduardo.

Eduardo was the shortest of the brothers, but even as a seven-year-old he stood out. Soon he had been christened Tostao, the little coin. Unlike Pelé, he must have liked the name. There are no stories of psychological wounds, only an apologetic smile. ‘I can’t remember when and why it started.’

By the time he was fourteen, Tostao was playing junior football for Cruzeiro. By the age of sixteen he had signed professional terms at América – his father was no longer on the books. As he passed through his apprenticeship Tosta^·o found time to keep his head in his books. ‘I had cultural notions, I liked to read, I liked to study,’ he says.

At eighteen, marked out as what he calls a grande promessa, Tostao had to choose the direction his life was to take. Until then his opinion of football as a profession had been characteristically white-collar. ‘Football was like a paid entertainment,’ he says. Blessed with intelligence and a sense of his own God-given ability, he opted to leave his studies, at least for a few years. ‘It was worthwhile because I had everything to be a great player. I was aware that it would be for a short time and my future life would be different,’ he says.

A natural goalscoring centre-forward, Tostao quickly emerged as the great meteor of the Brazilian game. His intelligence and all-round ability was soon winning him comparisons with Pelé. In 1966 he was called up to the Brazilian squad as the King’s prince in waiting. At nineteen, he was little over half the age of some of Feola’s veteran squad.

He made his World Cup debut as replacement for Pelé in the Hungary match. His baptism was memorable for the explosive left-footshot he fired past the Hungarian keeper Gelei, but eminently forgettable in every other sense. He grimaces at the memory of the humiliations that followed. Tostao lays the blame on the lack of organization and basic physical fitness.

‘From the group of 1958 and 1962, the only one who was in condition to play was Pelé. Djalma Santos, Gilmar, Bellini, Orlando, Garrincha, no,’ he says, shaking his head. Tostao had heard the stories about Garrincha’s alcoholism but still found his disconnection from reality hard to believe. ‘They said that Garrincha didn’t even know who the opponents were in the Final in 1958. In England Garrincha was in no condition at all and played.’

He left England regretting that Feola had failed to listen to those, himself included, who believed that rather than being his understudy, he should be Pelé’s partner. It had been in a warm-up match in Sweden on the way to England that Tostao had sensed he had found a kindred spirit. ‘It was a friendly game and we understood each other immediately,’ he says. ‘He needed a more intelligent player at his side, a player that understood where he was going to be.’

It is perhaps his greatest footballing regret that they didn’t play together more frequently. ‘Today the Brazilian squad meets every month. In my time it was not like that, we played two or three games a year. If I had had the opportunity to play in the same team as him, our partnership would have been richer.’ It was not only Tostao’s loss, it was the world’s too.

Tostao’s journey to Mexico was at times unbearably eventful. He was the unquestioned hero of Brazil’s qualification campaign under Saldanha. His all-round contribution was as profound as it would be in the finals. During the team’s travels around South America and back in the Maracana in August 1969, however, it was his phenomenal goalscoring ability that set his countrymen’s hearts racing.

He had forced his way into Saldanha’s side with his display against England in June that year. Ramsey’s men arrived from Mexico with an unbeaten tour record and a quiet confidence that they could strike an early psychological blow against the side already being trumpeted as their most serious rival the following summer. Brazil emerged with the mental edge, after a convincing 2–1 win in which Tostao scored a spectacular winner.

As the ball had broken loose in the English defence, Tostao seemed to pose no threat as he lay prostrate on the pitch. Seeing the ball moving towards him, however, he levered his lower body off the grass with his arms and executed a mid-air scissor-kick that sent the ball crashing home. Back on Fleet Street, photographs of Tostao levitating himself to manufacture a barely believable goalscoring shot was used as chilling evidence of Brazil’s rediscovered divinity.

Years later Tostao was shown copies of the back-page eulogies he received. ‘The people didn’t understand how I scored that goal,’ he says, a boyish smile breaking across his face. The goal proved a portent of things to come that summer.

From the moment he pounced on the Colombian keeper Lagarcha’s parry of a Pelé free kick in the thiry-ninth minute of the opening elimanatoria match in Bogotá, Tostao was in the most lethal form of his international career. He scored the second in the 2–0 win in Bogotá and four days later broke the deadlock against the Venezuelans in Caracas. Tostao left the defenders Chico and Freddy floundering before finishing with a cool shot, thirteen minutes from time. In the remaining quarter of an hour he and Pelé ran riot, first Tostao setting up his partner for the second then scoring the third and fourth goals himself.

His form continued back at the Maracana. He scored two more in the 6–2 win over Colombia but saved his finishing masterclass for the decisive win over Venezuela on 24 August. His hat trick within 24 minutes took his tally to ten in four matches and his team to Mexico. Pelé scored the only goal in the final match against Paraguay. By the end of the month the duo had scored fourteen goals in five games between them.

Tostao’s free-scoring performances won him the headlines normally reserved for Pelé. In Europe, where he had only flickered in 1966, the White Pelé became the symbol of the new, revitalized Brazil. Soon he would symbolize the fragility of his nation’s confidence instead.

Tostao’s career – and so his life – was transformed during a Corinthians v. Cruizeiro match in late September 1969. In a freak accident he was hit in the face by a ball from Corinthians full-back Ditao. Such was the force of the impact he could not see afterwards. In hospital he was diagnosed as having suffered a detached retina.

Drawing on his own connections, Tostao engaged one of Belo Horizonte’s most eminent medical figures, Dr Robert Abdalla Moura. On 3 October all Brazil held its breath as Tosta^·o and Dr Moura flew to Houston to undergo potentially risky surgery to the eye. Moura performed the operation himself at the Santa Monica Ophthalmology Center in Houston and returned to Brazil to pronounce himself pleased with the results.

The following months were agonizing for Tostao. In April 1970, on the Friday before he was due to make his comeback against Paraguay in the penultimate warm-up, Tosta^·o woke up in bed in Belo Horizonte with blood streaming from his left eye. At first his bad luck looked like Dario’s good fortune. Instead the game ended a goalless draw and both teams were jeered off the pitch. It proved the last time the President’s favourite wore the No. 9 shirt and reminded Zagalo how priceless Tostao was to his side.

At first Zagalo had to be convinced of Tostao’s importance to the campaign. ‘When Zagalo took over he was soon saying that I was a reserve to Pelé. Up front he said he needed a player of speed,’ Tostao explains. As the manager watched the team at work in practice in the warm-up matches and began to switch Saldanha’s 4–2–4 formation to a more flexible 4–3–3, however, Tostao’s importance to the side became clear.

Like Rivellino, Piazza and Jairzinho, Tostao was asked to adapt his natural game to fit into the plan. His sacrifice was, perhaps, the greatest of all. Zagalo asked Tostao to suppress his predatory instincts and act as a sophisticated target man instead. He would spend much of the Mexican campaign with his back to goal, flicking and stroking off a range of simple and subtle passes to Jairzinho and Rivellino, Pelé and Gérson. ‘They needed somebody to organize the game up front. I was the pawn,’ he smiles.

Yet when he joined the squad at Guanajuato, there were those – Pelé included – who doubted whether he was physically and mentally up to the challenge ahead. Their fears were understandable. Tostao cut a sensitive, secretive figure at the training pitches. Back in Brazil even President Médici had been expressing his public concern at his fitness. At the sight of a quote-hungry journalist he would hold up his hands and plead ‘Please don’t ask me about my eye’. Within the camp his insecurity became unsettling. Publicly Pelé expressed confidence that his friend would pull through. Privately he harboured serious doubts. What else was he to think when he saw Tostao unwilling to head a ball in training? ‘They were a little bit apprehensive, scared that I was not well,’ he nods, pouring some more coffee as he speaks.

Two weeks before the first match he suffered an attack of conjunctivitis. As Dr Abdalla spent a day examining him he offered to withdraw so Zagalo could draft in a replacement. ‘I said: “If you are not confident that I can play you should fire me and I would understand”.’

Tostao’s friendship with Piazza allowed him his peace and quiet in their room. While Piazza made himself scarce, Tostao would spend hours dismantling and studying a large, plastic medical school model of an eye he had been given by Dr Abdalla. The model helped him overcome his fear. ‘We are only frightened when we don’t know what we are suffering from. I know my problem very well,’ he told reporters philosophically at the time. Dr Abdalla remained in Guadalajara and, with Tostao’s parents, was a frequent visitor to the Suites Caribes.

As his strength and confidence returned, his patience with the press had seemed to mirror his renewed determination. ‘If I give up now, I will never play football again and I will never feel self-confident any more. I cannot give up. Am I a man or a mouse?’ he had said, a new defiance in his voice.

Tostao had been the team’s touchstone the previous August. Not a man for idle boasting, when he began to talk of Brazil winning his confidence spread through the camp. Even today he can recall the calm certainty he felt in the final days before the opening match. ‘It is not something I can explain, it is something deep inside. I am a very intuitive man. I always have a feeling when something good or bad is going to happen and rarely am I wrong.’

Despite the traumas of the preceding months, Tostao fulfilled all his potential in Mexico. He was perhaps the most consistent of all the team. Yet when he puts his own performances in the World Cup under the microscope, his hypercritical mind finds them wanting. As far as he is concerned he made three ‘great moves’ in the tournament. ‘If I left those three moves out I would say I played badly – sincerely.’

He scored two goals against Peru – the first an impudent shot inside Rubinos’ near post, the second a scooped shot high into the netting from a dangerous cross-cum-shot by Pelé. Yet he discounts them both. ‘The two goals I scored were two simple goals, nothing exceptional,’ he says. ‘The rest of my contribution was important tactically, very important without doubt, as a pawn.’

Watch Tostao score against Peru in Mexico 1970

He admits the first, the ‘nutmeg’ of Bobby Moore which led to Jairzinho’s goal against England, owed as much to panic as premeditation. He had seen Zagalo warming up his replacement Roberto on the touchline and realized he would have to pull out something special just to remain on the pitch.

‘Without doubt it was the most difficult match because England annulled Brazil’s moves. Tactically England were perfect, it became a chess match,’ he says. ‘Roberto was warming up. I thought “He’ll replace me so I must do something now”.’

He had already had a shot deflected when he picked up the ball again on the left. His twisting, turning run took him through Moore’s legs and away again. His back was turned to the goal, yet his swivelled cross travelled deep into the crowded English area and straight to the feet of Pelé. Pelé sucked in the defence before unloading the decisive pass to Jairzinho. Even the telepathic twosome had never managed quite such a psychic connection. In the elation that followed Jairzinho’s goal, however, Tostao was still substituted. ‘They had signed the papers, before the goal,’ he smiles. ‘But there is no doubt the substitution was a stimulus for me to try something different.’

He is far prouder of his crucial contributions in setting up Clodoaldo and Jairzinho’s goals in the semi-final against Uruguay. Amid the fireworks of Pelé and Rivellino, Gérson and Jairzinho, the moments are hardly ones that blaze away in the memory. Both were perfectly weighted, inch-accurate through balls rather than moments of extemporized goalscoring. That he should choose these two moments above all others is perhaps the ultimate testimony to his philosophy as a footballer. For Tostao both were triumphs of substance over style.

‘Clodoaldo ran and shouted to receive the ball in front of him. I was able to wait a few seconds so he could arrive in the right position,’ he says of the first. For the second he had to place a ball in a tiny two-metre space between the advancing Jairzinho and a retreating defender. ‘I was very conscious that if I gave the pass in front of the defender he would arrive first. So I gave the pass in front of Jair and behind the defender. When Jair controlled it the defender tried to turn, lost control and Jair went on and scored,’ he says.

‘I’m more proud about them than the move against England because there it was completely emotional. In the two against Uruguay I had the clear sensation of the consciousness of the move.’

Given the dramas that had befallen him en route to Mexico City, the sensitive Tostao found the Final almost too much to bear. He had been a restless sleeper throughout his career. ‘When journalists asked me how I was before an important game, I would say “I’m very well, confident”,’ he smiles. ‘The truth was I was extremely tense, I didn’t sleep well because I was preoccupied, thinking.’ He admits he barely slept during the stormy night of 20 June.

Tostao’s respect for Gérson was enormous. ‘Carlos Alberto was the captain, the great leader was Gérson,’ says Tostao. Of all the side, he was the player in whom he felt he could confide. ‘I liked him very much. We would sit up until three or four o’clock in the morning talking,’ he says. The two men sat up late on the night before the Final, each calming the other’s nerves.

The Final represented Tostao’s ultimate sacrifice. He had been involved in the discussions about how to turn Italy’s man-marking system to Brazil’s advantage. ‘It was the most clear example of the group working together,’ he says. As well as the ruse to draw Facchetti out of position, Zagalo and his team sensed that Tostao’s ability off the ball might be able to create precious space for his midfield colleagues too.

‘We agreed that I would play far in front. I would not go back to receive the ball, I should stay with the spare defender, obliging him to stay with me.’ The plan worked perfectly during the opening phase of the match as Rosato played the unwitting consigliere to his Godfather, shadowing his master’s every move. As Tosta^·o buzzed around amongst the back three, Rivellino and Gérson duly discovered the Azteca opening up to them. ‘If Rivellino had been on top of his game he would have scored at least two goals from outside the area. I think he put five shots over the bar,’ Tostao says with a rueful smile.

The Platonic principles at work within the side had borne remarkable fruit on the way to the Azteca. But perhaps nothing summed up the collective spirit better than Tostao’s supremely selfless contribution to the Final. His intelligent runs off the ball kept Rosato and the Italian defence guessing all afternoon. ‘My pleasure was to play with the ball but against Italy I was playing without the ball,’ he says.

Tostao even appeared in the penalty area to clear the lines at one moment of danger in the second half. We also tend to forget that the famous Carlos Alberto move was begun when Tostao, running himself into the ground in the dying minutes, dispossessed an Italian deep in his own half.

All of us who witnessed it remember the Final for the beauty of that closing phase of play. Gérson and Jairzinho’s goals paved the way for a flourish that embodied all the qualities that had made the Brazilians the most admired and loved side in the history of the tournament. Tosta^·o’s memories too are dominated by the sheer emotion of its climax. After Jairzinho scored the third goal and he knew the game was safe he admits he could contain his feelings no longer. As the sun poked through, the pitch had begun to dry. Tosta^·o’s tears were soon dampening the lush Azteca once more. ‘I played the last fifteen minutes crying,’ he confesses, wiping the moisture from his eyes as he speaks.

When the final whistle went Tostao became, with Pelé, the focus of the crowd’s adulation. The two had turned to each other and embraced. As others ran for cover they were swamped by the throng. Tostao’s initial joy soon gave way to fear as Brazilian and Mexican fans ripped his boots, shirt, shorts and socks off him. ‘I was in the middle of the pitch. At first it was huge emotion but then I realized I only had my underwear on,’ he says. ‘I was in panic, the Mexican police rescued me.’ He was delivered to a dressing room convulsed by a crise de choro, ‘a crisis of tears’. It was only hours later that he began to absorb the full impact of what had happened.

With Pelé and the rest he had gone out to the official party at the Hotel Isabel Maria on the Reforma in the centre of Mexico City. Once more the players found themselves besieged by elated Brazilian and Mexican fans and had to virtually fight their way into the party. The popular Brazilian singer Wilson Simonal had been hired to sing. Carlos Alberto led the dancing as the party went on until 1 a.m. on the Monday morning. Pelé, Carlos Alberto and Zagalo were among those who were summoned at one point to talk to President Médici on the telephone. All three struggled to hear a word he was saying.

Tostao stayed only briefly, however. He slipped out without a word and headed back to his room at the hotel. ‘I am a reclusive person. I wanted to be alone in my room,’ he says simply.

Tostao gave his medal and his No. 9 shirt to Dr Abdalla as a mark of thanks. As he returned to Brazil a national hero, his beloved solitude – and peace of mind – were commodities he would find increasingly hard to come by.